Warren Newcombe

(1894 -1960)

From Special Effects to the American Scene:

The Life and Times of an American Artist and Designer

Jeffrey Morseburg

Warren Newcombe was a painter, printmaker, experimental filmmaker and an innovative, Academy Award-winning special effects designer and studio executive. He was trained as a traditional fine artist in the elegant Boston School tradition. Newcombe painted sophisticated portraits initially, then worked his way to his own version of 1930s "American Scene" Regionalism while he worked as an important special effects artist Hollywood.

During the interwar period, when Newcombe's career was at its peak, his paintings and prints were widely shown in solo and group exhibitions in some of America's most prestigious art galleries and museums. Today, his work is found in the permanent collection of a number of major museums. However, in the world of film he will always be best known for his development of the "Newcombe shot," which was a key component of "movie magic" during Hollywood's "Golden Age." During his forty years in the film business, Newcombe collaborated with some of the greatest directors in cinematic history, from D.W. Griffith and King Vidor to George Cukor, William Wyler and Vincente Minnelli.

Early Life and Artistic Training

Warren Alfred Newcombe was born on April 28, 1894, in Waltham, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston. His father, William Alfred Newcombe, worked for a piano company while Warren was a boy, and his mother, Minnie C. Newcombe, was a homemaker. His mother was a native of California and his father was a Canadian immigrant from Nova Scotia. His parents separated for a time during the artist's youth, but by Warren's teenage years, the family was reunited and his father eventually became a high school teacher.

Young Warren was always artistically inclined, and he became an artistic prodigy with a wide variety of talents and interests. Fortunately, for an aspiring artist, Boston was an excellent place to gain a formal artistic education. It was a highly cultured city and a significant center for art, home to the group of academically trained American artists that became known as the "Boston School."

Joseph Rodefer de Camp (1858-1923), Frank Weston Benson (1862-1951), Edmund C. Tarbell (1862-1938) and William McGregor Paxton (1869-1941), were brilliant portrait and figurative painters, all of whom believed in teaching; passing on what they had learned in the ateliers of Munich and Belle Époque Paris to younger artists.

Warren Newcombe studied in the cramped quarters of the Boston Normal Art School, which many of the major Boston artists had attended when they were young. While the Normal Art School is little known today, at one time it was among the most important and influential art schools in America. Inspired by European models, Massachusetts had opened a series of "Normal Schools," which were specifically dedicated to the training of teachers. These gradually evolved into teacher's colleges. The Normal Art School was opened in 1873, and given the mission of training art teachers. This meant not simply the training of fine artists and commercial illustrators who could turn to teaching, but the Normal Art School placed an emphasis on developing a curriculum that enabled its students to teach art to children.

Joseph de Camp was Newcombe's teacher and mentor at the Normal Art School. Like all of the portrait painters from the "Boston School," Joseph de Camp was a brilliant draftsman. When he took over the portrait program at the Normal Art School in 1903, the school had begun to shift its emphasis, and an increasing number of students were enrolling with the intention of becoming fine artists rather than teachers. Newcombe's early works, especially his portraits, show the stamp of de Camp's elegant influence.

After graduating from the Boston Normal Art School in 1914, Newcombe began teaching and did illustration work. He taught in Lynn and Brookline, Massachusetts, but his teaching career only lasted for a short time. He then worked as a magazine and book illustrator. No illustrations by Newcombe have yet been discovered in the pages of any of the national magazines that made an extensive use of illustration, but as a less established young illustrator, he may have also done un-credited works for a commercial illustration service or for one of the hundreds of smaller, regional publications that also depended on illustrations.

The Film Business

Warren Newcombe was destined to become one of the most important figures in the specialized craft of painting for motion pictures, but his first work for a film production was in in his native Boston in 1918, when he designed sets for an Atlas production. Atlas Film Corporation was a film company that was chartered in Massachusetts while a number of film production companies were still based in the Boston area. In 1920, and 1921 Newcombe worked as an artist and designer for the pioneering film producer Louis Selznik (1870-1933) in Ft. Lee, New Jersey, where many early film studios were located. He was also painting in and around New York at this time, experimenting with the urban landscape, such as the extant 1920 Newcombe work titled Queensboro Bridge, which shows the influence of the realist painters from Philadelphia and New York that we know as the "Ashcan School."

Newcombe also worked on the courtroom melodrama, The Woman God Changed, with screenwriter Clarence Doty Hobart (1886-1958) in 1921, probably after he left the Selznick studios. Newcombe was then in the process of developing his own techniques for matte painting. He also did an elaborate new title sequence for the 1922 re-release of Enrico Guzzzoni's (1876-1949) Quo Vadis (1912). Now little known, the 1912 film was a cinematic landmark. He was also credited for work on The Headless Horseman, a Will Rogers version of Washington Irving's story.

Sometime in the early 1920s Warren Newcombe created the matte painting technique that is still known as the "Newcombe shot," a seamless method of meshing live action film footage with flat "matte" paintings; one that went well beyond the matte techniques used in earlier productions. He used the pastel medium to create highly realistic scenes, which were used in post-production to make it appear as if a film was shot in another location or even another era. With "Newcombe shots" anything an artist could visualize and bring off artistically, using pastels or paints, could become a new background for a scene. With Newcombe's technique, the live action and the matte painting were filmed separately and then combined in post-production.

Warren Newcombe was not content to simply assist directors and producers in putting their visions up on the silver screen. He set out to create his own eclectic short films while he did work for a number of productions in his own New York studio. In 1922, he released The Enchanted City and then The Sea of Dreams, in 1923. Both releases are now considered major contributions to the field of experimental film. Newcombe's short films melded his pastel fantasies with live action sequences and brought a sort of dreamy, soft-focus Camera Pictorialist vision to moving film. No one would have dreamt that there was significant commercial potential in these "art films," but they served as a visual calling card or resume for a cinematic artist who had rapidly become a master of the new medium. But for Newcombe, there was another added benefit to the short films - on June 14, 1924 he married the actress Hazel Lindsay, the star of Sea of Dreams.

D.W. Griffith hired Warren Newcombe in 1923, perhaps after seeing what the artist was capable of in The Enchanted City or Sea of Dreams. Born to a poor but distinguished rural Kentucky family, David Wark Griffith (1875-1948), grew up to become the single most important figure in the history of film. By 1919, Griffith felt Southern California was already overexposed on film, so he fled Hollywood and studio supervision by moving back to New York, where he built his own studio on Long Island, where Newcombe helped design some of the elaborate sets. Newcombe then did matte paintings for Griffith's last great historical epic, America, a Revolutionary war melodrama. In order to make the location shots that were filmed up and down the east coast and the filming done on Griffith's Mamoronek studio lot look like they occurred in the 18th century, many matte paintings were required, and so Newcombe's work became an essential and credited part of the complicated production, one of the earliest production credits for specialized matte paintings.

Hollywood Beckons

Newcombe and his wife, Hazel, moved west in 1925, where they settled in Santa Monica, and he joined the staff of MGM's art department. This was soon after Louis B. Mayer (1884-1957) merged his company with the larger Metro and Samuel Goldwyn companies, to form Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the greatest studio in cinematic history. On MGM's vast Culver City lot, he worked under the legendary art director Austin Cedric Gibbons (1893-1960), who ran the MGM Art Department with a firm hand, but allowed his department heads the autonomy they needed to do their jobs properly. Gibbons had four hundred talented artists, artisans and craftsmen working for him when the company was at its peak, producing forty to fifty films a year. Newcombe was responsible for developing the techniques and supervising MGM's new matte painting unit, where he used his own techniques, which were guarded with rigorous secrecy, even from the studio bosses.

In 1925, Newcombe worked on director King Vidor's (1894-1982), The Big Parade (1925), Hollywood's first major war epic and the model for most of the big-budget war films that have followed. The Big Parade was a lavishly made film, but in Hollywood's studio system there was little remote location shooting, which was a tremendous expense. This meant that everything in the film, from a scene where a character works as a steelworker on a high-rise, to scenes of artillery-battered French villages, lines of Allied and German trenches and the barbed-wire filled "no-man's land" between them, had to be believably re-created on the MGM back lot and sound stages. In order to bring the beautifully designed and constructed sets to life, the upper half of countless scenes were masked off when they were filmed, so that Newcombe and his co-workers could paint mattes to depict the bomb-ravaged upper stories of a French farmhouse or jagged roof of the shattered cathedral that sheltered the wounded; what film veterans called "extending the set." Newcombe's matte work was essential in bringing Vidor's cinematic vision to life and his matte unit was to do the same quality of work on hundreds of productions for the next thirty years.

Warren Newcombe's Artistic Development

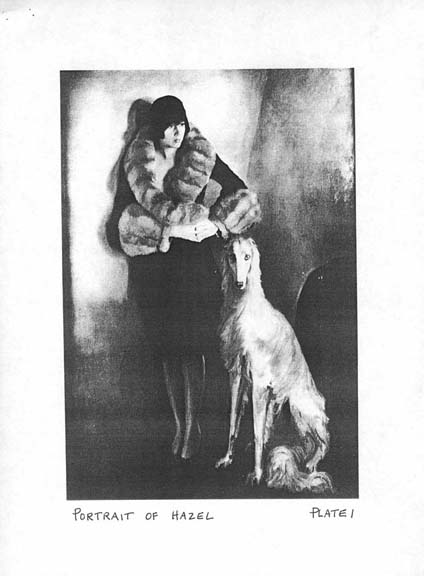

Despite Newcombe's tremendous responsibility for MGM's never ending slate of feature films, he painted vigorously in his hours away from the studio. painter's progress is often a crooked path rather than the type of straightforward course that we may like to imagine. Newcombe was trained in the solid, well-drawn, beautifully painted tradition of the Boston School, and it is clear that he was happy working in this manner for some time. Hazel and Big Boy, or Portrait of Hazel, the stylish, grand portrait he painted of his wife in 1926, after he had settled in Southern California, is immediately recognizable as a Boston School painting. However as he read about painters and artistic movements of the late 19th and early 20th century, he realized that he wanted to do something different and began a period of intense experimentation

By the late 1920s, Newcombe was struggling with the influence of early European Modernists such as Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973). He worked to incorporate some of their ideas, concepts, and their visual idiom into his own painting. He created a number of starkly modern paintings, including Kundry and Parsifal (1927) and Isolde (1928) that betray the influence of the Germanic Symbolists and these works can be described as having an Expressionist quality. Newcombe also went through a phase where he came under the spell of Cezanne and Matisse, and the result were paintings such as Red Table (1929) and Woman and Fanback Chair (1930). Gradually, it became apparent to Newcombe that he would never come to fully embrace abstraction or be happy hewing closely to the course of a short-lived European movement like Fauvism or Cubism. Instead, he returned to painting the types of works he experimented with the early 1920s, when he painted contemporary subjects, paintings of the man-made world that surrounded him.

Warren Newcombe and the Dawn of the Regionalist Vision

As the 1930s dawned, Newcombe's paintings, like those of many other American artists, had become more stylized, resulting in an iconographic, even pictographic shorthand for the natural and man-made forms he painted. he works he was painting in the California Southland stood in vivid contrast to the atmospheric, painterly verisimilitude of the popular California landscape painters of the day. He no longer saw a need to render a landscape in a tender, poetic way or to add a measure of idealization to nature. Newcombe adopted a stylized method of painting the landscape, which relied on a forced perspective. His subjects were stripped of extraneous detail and rendered in bold strokes, using broad, flat planes of color. By the early 1930s, Newcombe was exhibiting locally with other painters who shared his artistic point of view, who also represented the style of painting that came to be referred to as "Regionalism," or "American Scene" painting.

Newcombe developed a close, collaborative friendship with the cultural impresario, Merle Armitage (1893-1975), in the early 1930s. Armitage had come west in the early 1920s and founded the Grand Opera Association and managed the Philharmonic Auditorium in Los Angeles, but from the 1920s through the 1960s, he seemed to have his hand in virtually everything to do with the cultural life of the Southland. In 1932, the Weyhe Gallery in New York City hosted a major solo exhibition for Newcombe, which Armitage probably helped arrange or organize, because a number of the other contemporary California artists and photographers that he collaborated with also had exhibitions there. Newcombe's exhibition was accompanied by a beautifully produced little catalog with a real lithograph on its cover. This small, beautifully produced catalog was one of the Renaissance man Merle Armitage's countless side projects. Although the Newcombe catalog listed Weyhe as the publisher, it was designed by Armitage and printed by the lithographer Lynton Kistler in Los Angeles and won awards for its design.

California Exhibitions & The Depression Era

Back in California, Newcombe had a series of solo exhibitions and exhibited his work with a number of new art organizations, most of which sought to combine representation with a more contemporary, modern vision. Newcombe had a solo exhibition at the Wilshire Art Gallery in 1929; then exhibited at the Pasadena Art Institute in 1930. He then sent his work to a group exhibition at the Opportunity Gallery in New York and was invited to participate in the Corcoran Gallery's 12th Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting in Washington D.C in the fall of 1930. Newcombe also began long relationships with two influential dealers who shared his artistic vision, Earl Stendahl (1888-1966) who owned the Southland's most respected gallery, and Jacob Zeitlin (1902-1987), a pioneering rare book and print dealer and political activist.

Earl Stendahl hosted an extensive solo exhibition for Newcombe in 1931, and represented him for a number of years. But increasingly, as the 1930s dawned, he focused his artistic energies on printmaking, which seemed to offer fresh opportunities as the Great Depression deepened and fewer people could afford original paintings. Newcombe discovered stone lithography, where the composition is drawn in reverse on the stone using a lithographic pencil, and then printed. Because he did not have a background in the specialized field of lithography, he collaborated with two highly skilled California printers, Lynton Kistler and Paul Roeher (1878-1965), who actually printed the impressions once Newcombe rendered them on the stone. Newcombe's printings were small and exclusive and Zeilin's bookshop served as an outlet for his prints.

In 1934, Warren Newcombe began working with the Associated American Group, which was based in New York. AAG was a greeting card and print publisher that followed a concept pioneered by its competitor, Reeves Lewenthal's (1910-1987) Associated American Artists, a mass-market firm that changed the face of American Art. These companies, which were designed to look like some sort of New Deal artist's cooperatives, created tens of thousands of new art collectors through the magic of direct mail. Their print and card catalogs popularized the type of muscular American Regionalism that Newcombe and his compatriots were doing and they sponsored exhibitions at many regional art museums. The artists who worked with the American Artists Group included a number of the most iconic artists of the regional movement, including Grant Wood (1891-1942), John Steuart Curry (1897-1946) and Rockwell Kent (1882-1971).

As American Regionalism was promoted by Associated American Artists and was championed in the pages of Life Magazine, it soon won acceptance from museum curators as a uniquely American art movement. Newcombe's work, his original paintings, as well as his lithographs, were exhibited across the United States, from the Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, to the Cincinnati Art Museum and Chicago Art Institute in the Midwest to the Whitney Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in the East. The Pennsylvania Academy purchased one of his major works, a painting of Greta Garbo on a movie set, for their permanent collection. He also had solo exhibitions locally at the Pasadena Art Institute, the Warner Gallery in Westwood, as well as the Stanley Rose Gallery in Hollywood and the Centaur Gallery in Los Angeles. Newcombe showed with the Los Angeles Fine Arts Association and the Foundation for Western Art locally as well as the Society of Independent Artists and the American Artists Congress nationally.

The Golden Age of M-G-M

From the mid-1930s on, Newcombe was formally listed as the head of M-G-M's Matte Painting Department, which was often listed organizationally under Buddy Gillespie's Special Effects Department, as matte paintings were a key component of the "movie magic" of special effects. However, Newcombe's unit was more or less autonomous and he exercised control over a number of skilled matte painters and the team of photographers who shot their work. Because of the hierarchical system at M-G-M, the artists who worked under Newcombe were rarely, if ever, credited and we only know the names of the artists who worked under him from the diligent work of writers and researchers and from the notes on the studio mattes that have surfaced. Because they worked at a headlong pace, averaging about forty productions a year, the number of films that Newcombe supervised matte painting work for is dizzying, but the legendary Wizard of Oz may have marked the peak of his career.

The Wizard of Oz was probably the most complicated production that Newcombe and his crew ever tackled. The artist was intimately involved in the production, supervising the matte unit and contributing so many other ideas and concepts that he also received a film credit as a "Set decorator." There was a seemingly endless number of his patented "Newcombe shots" to paint and then photograph. In one memorable scene, we see the characters as they march through the stylized poppy fields down the Yellow Block Road, on their way to Emerald City, its skyline gleaming in the distance. In a typical matte shot like this, only the characters were filmed in live action, while a member of Newcombe's team of matte painters painted the rest. However in The Wizard of Oz, a number of the matte shots were much more stylized than the typical mattes of the era, which were aimed at verisimilitude rather than artistry, but these were fanciful and artistic.

Thanks to the work of the miniature crew, the trick photography of the rear projection unit and the "Newcombe shots" of the Wicked Witch's castle, the panoramic shots of the Emerald City, the city's gates, the Wizard's throne room and finally, the Wizard's rising balloon as he makes his getaway, The Wizard of Oz was considered a technological marvel. If we use an artist's eye to look at some of the matte work that appears in the finished film, rather than the eye of a delighted adolescent, we can see that the landscapes are really American Regionalism writ large, a Warren Newcombe or Grant Wood landscape on the big screen.

While World War II descended on Europe in 1939, the United States only entered the war after Pearl Harbor. Even though many actors and studio employees entered the service, the government considered film production a vital distraction and MGM's slate remained full throughout the long conflict. Its wartime films were a mixture of escapist fantasies and patriotic productions. Westerns were never a staple of Mayer's studio, but Newcombe worked on the Robert Taylor (1911-1969) horse opera, Billy the Kid (1941), and then Victor Fleming's remake of (1889-1949) Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941), which starred Spencer Tracy (1900-1967). He then supervised the special effects for the wartime classic Mrs. Miniver (1942).

The great World War II film, Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, a wartime Mervyn Leroy production, remains a classic. It was one of MGM's creative department's finest wartime collaborations and Newcombe's matte painters were a large part of the film's success. Spencer Tracy (1900-1967) starred in the film, which was inspired by Col. Jimmy Doolittle's (1896-1993) famous 1942 raid. Newcombe supervised the exceptional matte work and his compatriot, Donald Jahrus, was in charge of the incredible miniatures. MGM's huge water tank was put to good use and George Gibson's scenic department painted a sixty-foot backdrop for a scene of Doolittle's planes being launched from the U.S.S. Hornet. The matte shots that Newcombe's men provided for shots of the Hornet's flight deck were flawless and even today, it is impossible to see the line of delineation between the matte paintings and the live action. The Motion Picture Academy realized the value of the film's technical units and A. Arnold Gillespie, Donald Jahraus and Warren Newcombe shared an Academy Award for Best Special Effects at the 1944 Academy Awards, the matte artist's first Oscar.

Post War

Green Dolphin Street (1947) was an MGM blockbuster that was advertised as a motion picture epic in the tradition of Gone with the Wind and Mutiny on the Bounty. The Academy did not seem to be impressed by the story or the acting, but at the 1948 Academy Awards, Green Dolphin Street was nominated for Oscars in four technical departments. Warren Newcombe, A. Arnold "Buddy" Gillespie, Douglas Shearer and Michael Steinore were awarded an "Oscar" for the Special Effects, which was Newcombe's second and final Academy Award. But in post-war America, times were changing and Hollywood would have to change with it.

Looking back on his long career, the publicist Edward Lawrence realized that 1948 was the last great year of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio. "From then on, the studio was like a patient with a chronic illness, kept alive by timely blood transfusions until the blood bank ran dry." After the war, when people returned to work and millions of young couples started families, box office figures started to drop. The steady spread of television to more and more homes, only exacerbated this decline. At the same time, there was a new interest in a more realistic approach to story-telling and filmmaking, so the industry moved to what was described as "Neo-Realism," an approach that did not sit well with Louis B. Mayer and the studio that had released The Wizard of Oz.

While RKO Studios was known for its lavish "Fred and Ginger" musicals in the 1930s, MGM made a major contribution to this American art form as the cinematic musical was changed, as it moved away from the whipped cream Art Deco sound stage fantasies of the Great Depression to more dramatic post-war stories, where the musical numbers were often used to advance the plot. The use of the Technicolor process and wide screen format allowed filmmakers to create a panoramic, wall-to-wall vision, where dance numbers were performed in true to life locations rather than the fanciful sets of a film like Top Hat (1935). The legendary Arthur Freed (1894-1973), who had begun his career as a lyricist and gained experience, as un-credited assistant producer on The Wizard of Oz, became the head of his own musical unit at M-G-M in 1939. Warren Newcombe and his matte department worked hand in hand with Freed and were an integral part of bringing his dozens of musicals to the big screen.

Newcombe also had a long and fruitful collaboration with Vincente Minnelli (1903-1986), the Chicago-born director, who was to become the premier director of movie musicals. He had much more influence on the look and art direction of his films because he began his career as a costume and set designer before making the leap to stage direction band then film. Minnelli was a stylist and each film that he worked with Newcombe and the M-G-M crew was exquisitely detailed. There are few directors who made better use of the wide screen. His films really need to be seen in the theatre where the elaborate sets, deep-focus photography and use of special effects can be fully appreciated. Minnelli was so focused on his artistic vision that some critics felt he could emphasize the look of his productions to the exclusion of everything else.

Newcombe first worked with Minnelli on Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), the film where the director and his leading lady Judy Garland (1888-1989), began the relationship that would result in the Minnelli family eventually having three Oscar winners. He also did special effects for Minnelli on The Clock (1945) and Yolanda and the Thief (1945). Newcombe and his unit had a major impact on the classic MGM musical Easter Parade (1948), the Irving Berlin (1888-1989) musical that was billed as the "happiest musical ever made."

Newcombe then returned to working with Vincente Minnelli on the Fred Astaire-Cyd Charisse (1922-2008) musical comedy, The Band Wagon (1953), one of the best-loved M-G-M musicals. Hollywood special effects historians speak of the special effects done for this film as exceptional, some of the finest examples of matte painting ever created. The incredible, sparkling neon signs on the Broadway theatres in the film are not real, but matte shots, with the "signs" painted on artist's board with hundreds of holes drilled through the board in intricate patterns so that the "neon lights," could be backlit and filmed with separate passes through the camera. Newcombe also supervised the special effects for Give a Girl a Break, a Stanley Donen musical the same year.

The matte painting department then completed its work for the Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz film The Long, Long Trailer (1954), which became a major hit. Newcombe supervised the special effects for the Lerner and Lowe musical, Brigadoon (1954) with Gene Kelly and Cyd Charisse. Science fiction was never a focus for MGM, but late in his career Newcombe worked on the kitsch classic, Forbidden Planet (1956), which starred the aging Walter Pidgeon (1897-1984), as well as young Leslie Nielsen (1926-2010) and Anne Francis (1930-2011). Directed by Fred Wilcox (1907-1964), Forbidden Planet is now considered a classic science fiction film with many of the conventions that are still with us today, including an interplanetary starship and Robby, a talking robot. Forbidden Planet was shot entirely on the MGM lot and the special effects were rated so highly at the time that Warren Newcombe was nominated for an "Oscar" for the last time.

By the late 1950s, almost all of MGM's executives from Louis B. Mayer himself, to Cedric Gibbons, his prolific art director, retired, their long reign at an end. Newcombe's last work before his career in Hollywood came to an end were Designing Woman (1957), a contemporary film starring Lauren Bacall (1924-2014) and Gregory Peck (1916-2003), the Stewart Granger (1913-1993) western, Gun Glory (1957) and finally, Edward Dmytryk's (1908-1999) steamy Southern Gothic melodrama, Raintree County (1957), with Montgomery Clift (1920-1966) and Elizabeth Taylor (1932-2011).

Newcombe's Personal Life and Last Years

Warren Newcombe's personal life is not well documented. He seems to have married three times, as he was listed as "married" when he registered for the World War I draft in 1917, when he would have been about twenty-four. He then married Hazel in 1924, after she starred in his short film Sea of Love. He had two daughters with Hazel; Hermine, born in 1935, and Sally, born about 1938. Warren and Hazel Newcombe were divorced in 1938 and he married Dorothy Macarthur in the following year, on a Tijuana getaway. He had a reputation as an eccentric and was considered to be difficult at MGM, so perhaps he was not easy to live with. Dorothy left him in 1951. Even though he made a generous salary, the financial commitment to his former wife and daughters, and then to his estranged wife and daughter, placed him in difficult financial position and in arrears to the tax authorities. In 1951 he turned to the court for relief and his plight became a national story that was picked up by the wire services.

With the heading: "Court Comes to Rescue of 'Oscar' Winner Squeezed Between Two Wives and the Tax Collector," and the sub heading: "Has Nothing Left out of $1,000 a Week," or "Alimony Troubles of the Too-Generous Husband," the storied told how Newcombe felt squeezed between his commitments to his present but estranged wife Dorothy and their daughter Sheila, and support for his former wife Hazel, and their daughters, Hermine and Sally. The beleaguered artist was also $27,000 behind in his income tax payments. The judge stated that: "In all the time I've been in domestic relations court, I've never seen a man who performed like this one. Here's a man who has been earning $52,000 a year for the past eight years and doesn't have a penny to show for it." With the Wisdom of Solomon, the judge split Newcombe's earnings, while allowing him something to live on himself.

Warren Newcombe retired from MGM in 1958 at the age of sixty-five. He was anxious to return to painting, his first love. When he was on a painting trip to Mexico in 1960, he died in the picturesque village of Taxco, apparently under mysterious circumstances, perhaps something to do with a relationship he had developed there, but the case was never solved. Newcombe is buried in Mexico City.

(Copyright 2014-2014, not to be reproduced without specific written permission and credit. Jeffrey Morseburg is an appraiser, archivist, researcher and writer.)

Memberships:

-American Artist's Congress

-American Arts Foundation

-American Artists Group

-Boston Guild of Artists

-Foundation for Western Art

-Society of Independent Artists

-Motion Picture Academy of Arts & Sciences, Charter Member

Permanent Collections:

-Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois

-Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

-Flint Institute of the Arts, Flint, Michigan

-Fogg Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

-Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

-Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California

-Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts

-Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

-Oakland Museum of California, Oakland, California

-Nelson-Atkins, Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri

-Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

-Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

-Weisman Art Museum, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota

-Wood Art Gallery, Montpellier, Vermont

Partial List of Exhibitions:

- Wilshire Gallery, Los Angeles, California, 1929 (Solo)

- Pasadena Art Institute, Pasadena, California, 1930 (Group)

- Zeitlin Gallery, Los Angeles, California, Paintings by Warren Newcombe, February

1930

- Opportunity Gallery, New York, November 1930 (Group, "San Gabriel Mountains," 1930)

- Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D.C., 12th Annual Exhibition of Contemporary

American Painting, November 1930-January, 1931 (Group, Red Table, 1929)

-Stendahl Gallery, Los Angeles, California, Exhibition of California Landscapes by

Warren Newcombe, November 1931 (Solo)

- Palace of Legion of Honor Museum, San Francisco, California 1931 (Group,

"Chatsworth Farm," 1931- Cincinnati Art Museum, 38th Annual American Art

Exhibition, (Group, "Arboles Verdes," 1931)

- San Diego Fine Arts Society, Sixth Annual Exhibition, San Diego, California, 1931

- Denny-Watrous Gallery, Carmel, California, Paintings by Warren Newcombe, 1931

- Pasadena Art Institute, Pasadena, California, 1932 (Solo)

- Marie Sterner Gallery, New York, New York, 1932

- Hollywood Assistance League, Hollywood, California: Warren Newcombe, 1932

- Del Monte Gallery, Monterey, California, Lithographs, 1932 (Group)

- Warner Gallery, Westwood, California, Lithographs by Warren Newcombe, December, 1933 (Solo)

- Los Angeles Museum of History, Science & Art, Los Angeles, California, Los Angeles Print Group, 1933 (Group)

- Museum of the Palace of Legion of Honor, San Francisco, California, November 1933 (Group, Prize)

- Stendahl Gallery, Los Angeles, California, Contemporary Prints, Merle Armitage Collection, April 1933 (Group)

- Society of Independent Artists, New York, New York, 1933 (Group)

- Los Angeles Museum of History, Science & Art, Los Angeles, California, 1934 (Group)

- Weyhe Art Gallery, New York, New York, 1933 (Group)

- Society of Independent Artists, 18th Annual Exhibition, Grand Central Palace, New York, New York, 1934 (Group)

- Weyhe Art Gallery, New York, New York, 51 Modern Prints, July, 1934

- Los Angeles Art Association, Los Angeles, California, 1934 (Group)

- San Diego Fine Arts Society, San Diego, California, 1934 (Group)

- Society of Independent Artists, New York, 1934 (Group)

- Rio Grande Art League, Harlingen, Texas, Lithographs by Warren Newcombe, Wood Engravings by Paul Landacre (dual)

- Los Angeles Art Association, All State Exhibition, Biltmore Salon, May 1934 (Group,

"Rancho de la Guerra") Whitney Museum of Art, New York, New York: 2nd Annual Regional Exhibition of Paintings and Prints by Artists West of the Mississippi, 1934

- Stanley Rose Galleries, Hollywood, California, Warren Newcombe Exhibition, December 1934 (Solo)

- Centaur Gallery, Los Angeles, California, Warren Newcombe, December 1934 (Solo)

- Grant Gallery, New York, New York, Paintings by Warren Newcombe, May 1935

- Foundation for Western Art, Los Angeles, California, Annual Exhibition, 1935 (Group)

- Corcoran Gallery, Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting,

Washington, D.C., April 1935 (Group Exhibition, #85 "Whitewater Wash," Palm Springs, California)

- Everhart Museum, Scranton, Pennsylvania, Selection of Paintings from Exhibition of - -- Contemporary American Painting, Washington, D.C., 1935 (Group Exhibition,

"Whitewater Wash," Palm Springs, California

- Colorado Springs Fine Art Center, Colorado, 1935 (Group)

- Denver Art Museum, Denver, Colorado, 1935 (Group)

- Los Angeles Art Association, Los Angeles Public Library, Prints from Weyhe & Company, (Group Exhibition, "La Casa")

- American Artist's Group, Bullocks Wilshire, November 1935 (Group Exhibition)

- Los Angeles Art Association, Los Angeles Public Library, Los Angeles, California, "Thumb Box" Exhibition, December, 1935

- Society of Independent Artists, Graphic Artists, Stendahl Gallery, November 1936 (Group, "Whitewater Wash")

- Grant Gallery, New York, New York, Paintings by Warren Newcombe, 1936

- Colorado Springs Fine Art Center, Colorado Springs, Colorado, American Artists West of the Mississippi, July, 1936 (Group)

- Foundation for Western Art, Annual Exhibition, "Trends in California Art," 4th Annual Exhibition, October 1936 (Group)

- University of California Art Gallery, Los Angeles, California, 1936 (Solo)

- John Herron Art Institute, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1936 (Group)

- Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Annual Exhibition, 131st Annual Exhibition, 1936 (Group)

- Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D.C., 15th Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting, April 1937

- Foundation for Western Art, Annual Exhibition, Los Angeles, California, California Graphic Arts, October 1937 (Group)

- Colorado Springs Fine Art Center, Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1937 (Group) ?-Denny-Watrous Gallery: Paintings by Warren Newcombe, December, 1937 (solo)-Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Annual Exhibition, 1937 (Group)

-Foundation for Western Art, Los Angeles, California, Annual Exhibition, 1st Annual Review of California Art, 1938 (Group)

-American Artists' Congress, Hollywood, California, Annual National Print Show-Los Angeles Public Library Art Gallery, Los, Angeles, California, 1938 (Group)

-Los Angeles Art Association, Los Angeles Public Library, Los Angeles, California, Three Man Exhibition, January, 1938 (Group, Vysekal, Lundmark, Newcombe)

-San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco, California, 1938 (Group)

-Whitney Museum of Art, New York, New York: 4th Annual Regional Exhibition: Paintings by Artists West of the Mississippi, 1938

-Los Angeles Museum of History, Science & Art, Los Angeles, California,

Contemporary Drawing, February, 1938 (Group)

-Werner Gallery, Westwood, California, 1938

-Faulkner Memorial Art Gallery, Santa Barbara, California 1938 (Group)

-Colorado Springs Fine Art Center, Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1938 (Group)

-Crocker Art Gallery, Sacramento, California, February 1938 (Group)

American Artist's Congress, Hollywood, California, Watercolors by Members, July 1938 (Group, "Chimney Beach")

- American Artist's Congress, Hollywood, California, Oil Paintings by Members, October 1938 (Group, "Ventura Dairy")

-Faulkner Memorial Art Gallery, Santa Barbara, 1939 (Group)

-Foundation for Western Art, Annual Exhibition, 1939 (Group)

-Colorado Springs Fine Art Center, 1939 (Group)

-San Francisco Museum of Art, 1931 (Group)

-Golden Gate International Exposition, San Francisco, 1940 (Group, "The Winery")

- Faulkner Memorial Art Gallery, Santa Barbara, 1940 (Group)

- Currier Gallery of Art, 1939 (Group)

- Crocker Art Gallery, Sacramento, California, 1938 (Group)

- Foundation for Western Art, Los Angeles, California, Annual Exhibition, 1940 (Group)

- Los Angeles Art Association, Los Angeles Public Library, Los Angeles, California, 1941 (Group)

- Foundation for Western Art, Los Angeles, California, Annual Exhibition, 1941 (Group)

- Los Angeles Museum of History, Science & Art, Los Angeles, California, 1942 (Group)

- Foundation for Western Art, Los Angeles, California, Annual Exhibition, 1942 (Group)

- Los Angeles Museum of History, Science & Art, Los Angeles, California, 1943 (Group)

- Oakland Art Gallery, Oakland, California, 1943 (Group)

- Los Angeles Art Association, Los Angeles Public Library, Los Angeles, California, Eight Southland Artists, June, 1943 (Group, "Movie Set")

- Foundation for Western Art, Los Angeles, California, Annual Exhibition, Los Angeles, California, July, 1943 (Group, "Whitewater Wash")

- Los Angeles Museum of History, Science & Art, Los Angeles, California, Group Show #1, September, 1943 (Group)

- Los Angeles Art Association, Los Angeles Public Library, Los Angeles, California, Lithographs by California Artists, Merle Armintage Collection, 1944 (Group)

- Foundation for Western Art, Los Angeles, California, Annual Exhibition, Watercolors by Anders Aldrin, Oil Paintings by Warren Newcombe, 1944 (Dual)

Biography from Papillon Gallery

Warren Newcombe was born in Waltham, Massachusetts in 1894. He studied, worked and exhibited as a painter and set designer in the United States, though a substantial Parisian influence is evident throughout his work.

Newcombe studied under Joseph DeCamp at the Boston Normal Art School in 1914. He went on to teach drawing in Massachusetts before moving to New York in 1918 where he supported himself as a commercial artist and portraitist.

Cinema and set design became an alluring career path as Newcombe joined Selznick Co. in 1920. Shortly after he built his own special effects production company and in 1923 produced the films The Enchanted City and The Sea of Dreams, both of which drew high acclaim.

In 1924 and 1925, Newcombe worked for D.W. Griffith designing sets and developing mechanics for filming difficult scenes. In 1925, he moved to California where he became the head of the special effects department for MGM Studios where he developed the widely used "Newcombe Process."

Newcombe is also credited for having designed such brilliant sets as the Emerald City in The Wizard of Oz and was awarded two Academy Awards for his work in special effects.

In the fine art world he continued to paint and exhibit regularly in Los Angeles and Carmel where he received two solo shows. He exhibited with the Society of Independent Artists and in galleries and museums in California, Texas, New York and Colorado. Newcombe contributed as well to various national art magazines and newspapers in the United States.

The artist died 1960 in Taxco, Mexico.

|