Irving Norman

1906-1889

Born Irving Noachowitz in 1906 in Vilna, which at the time was under Russia's control, Irving Norman emigrated to the United States in 1923, settling first in New York's Lower East, where he trained as a barber, and then in Los Angeles, where he opened his own barber shop in 1934. In 1938, Norman joined the Abraham Lincoln battalion of the International Brigade formed to help defend the Spanish Republic from the encroaching fascist dictatorship of General Francisco Franco.

Although he did not expect to survive the Spanish Civil War, he did, and in 1939, Norman returned to California, where he began to express through drawing and painting the atrocities he had witnessed during the war. The following year, Norman moved to San Francisco and enrolled in classes at the California School of Fine Arts. He quickly excelled, and by 1942, Norman had his first solo exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art. Four years later, Norman returned to New York and took classes with Reginald Marsh at the Art Students League. When he returned to the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1940s, he settled permanently near Half Moon Bay.

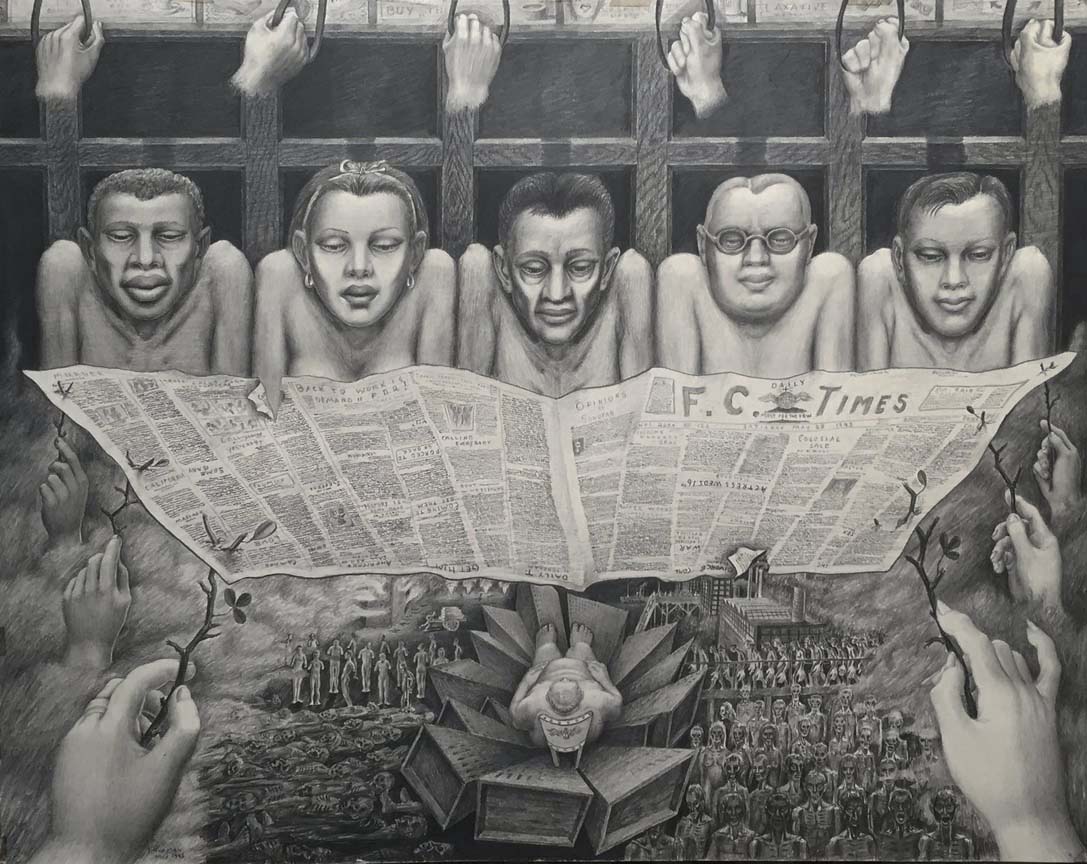

Norman's experience as a Polish-Jewish immigrant helped to shape his understanding of American society, and he often seemed to observe life in the United States with the shrewd and detached eye of an outsider. Over the course of his long career, Norman became best known for his highly detailed paintings, which offered powerful critiques of inhumanity and social injustice. Norman believed that by pointing out the cruelty, economic oppression, racism, and brutality enacted by both individuals and governments, viewers of his work might be moved to change society or at least to consider their own role in larger systems of power.

Influenced in spirit and style by Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siquieros - whose work he saw in Mexico in 1946 - Norman intended his paintings to be public art. Therefore, he shunned private patronage and avoided commercial viability and instead expressed the wish that his work be placed in public institutions, particularly museums, where "all people could come and study them and contemplate." Norman saw everything in human terms.

His paintings are monumental in scale, yet they teem with detail, populated by swarming, anonymous, clone-like figures. These generic signifiers of humanness are usually constricted by small urban spaces, caught in the crunch of rush hour, decimated by the pain of poverty, destroyed by the horror of war, trapped by the excesses of global capitalism. Such themes manifest Norman's perception of modern life and the society in which he lived, and his critiques of injustice are often animated by the artist's dynamic, off-kilter compositions, jewel-like colors, and piercing wit. Once engaged, the viewer cannot ignore or forget Norman's unsettling visions.

Always uniquely his own, Norman's paintings are nonetheless informed by a broad knowledge of art history, and they reveal the influence of numerous artists, cultures, and art movements. During decades overshadowed by pure abstraction, Norman focused on carefully detailed representational imagery and strong social messages. But his choice to buck dominant artistic trends only partially accounts for the fact that his work today remains relatively unknown.

Much of his earlier obscurity also stemmed from twenty years of surveillance by the FBI. Norman's youthful political affiliations marked him as a target for McCarthyist attacks on left-leaning intellectuals. However chilling the effect of such government scrutiny upon one man's life, Norman's paintings stand as a testimony to his talent, determination, unfaltering conscience, and to his ultimate belief in humanity. While often horrific and terrifying, Norman's colossal works contain a deeper message, and that is one of hope.

Biography from Michael Rosenfeld Gallery |